About R&T, Bad English, The Babys and solo

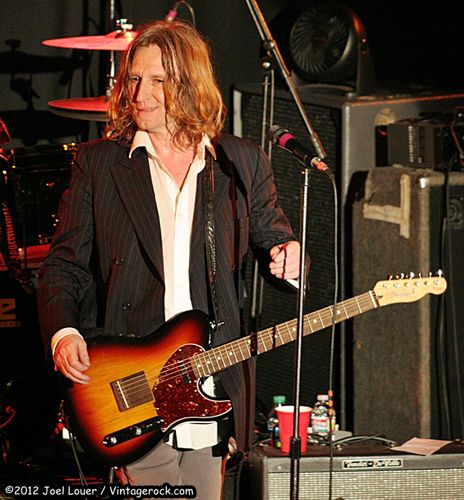

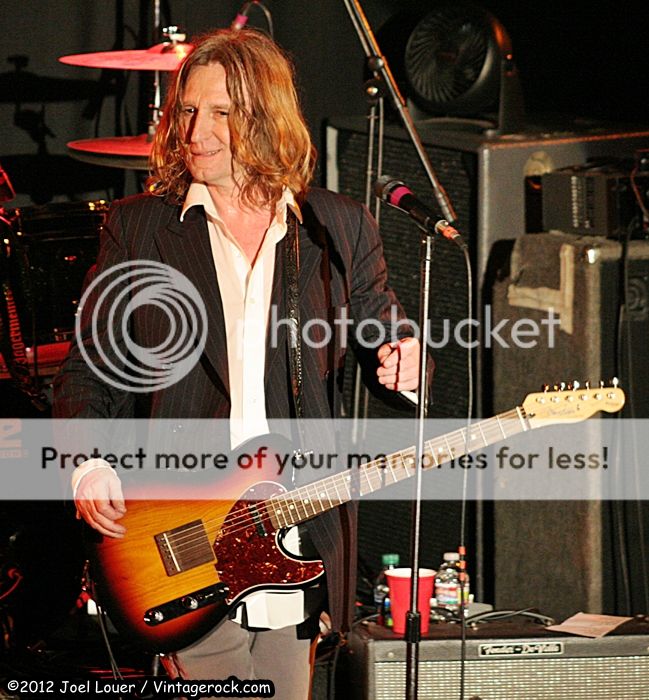

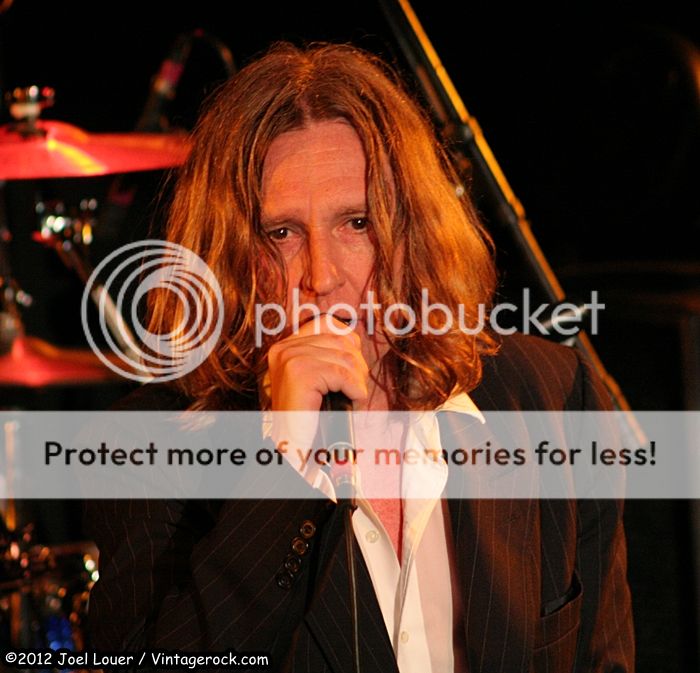

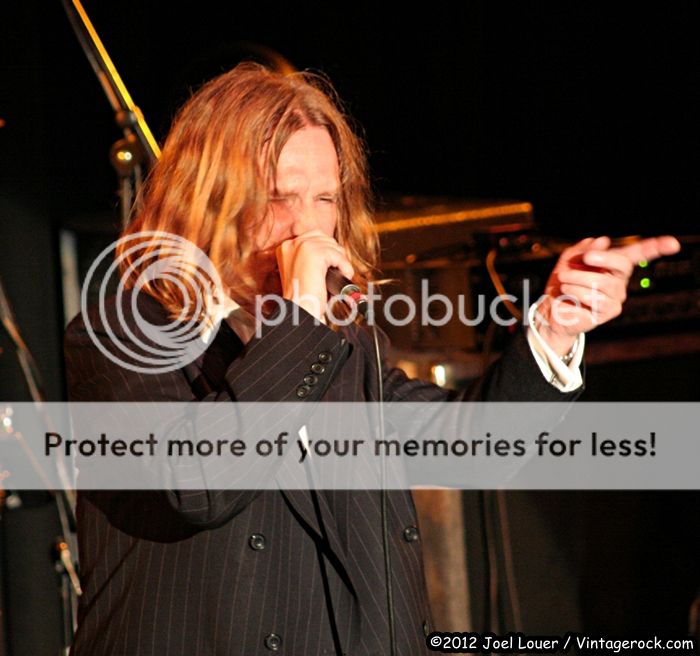

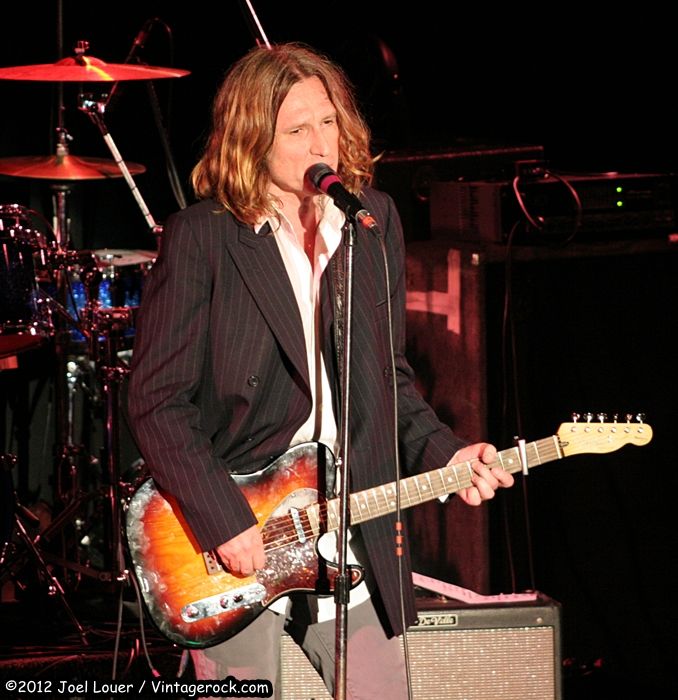

A Conversation with John Waite

Mike Ragogna: John, what inspired you to put a new album out?

John Waite: I did a European tour last year and I felt on stage that I needed really great new songs to sing. The energy was great and singing all of those big songs was great, but enough is enough. At a point, you have to put new stuff into the set. The stuff I've recorded recently is more introspective and singer/songwriter. You get a kick up the ass on stage in Europe. We do a lot of gigs in America, but the European gigs, they were really checking us out. I thought I should start upping the ante, so when I came back to America, I started work. Me and Kyle Cook from Matchbox 20 have been writing songs, and we went in and cooked those songs in Nashville, with Nashville musicians and Kyle on guitar. I took some time off, and that's when I went to Europe a second time and did another European tour. When I came back, there was some talk about getting more tracks done. I took my band in the studio and took seven songs and recorded them. It all seemed to work. I put those together with the songs that I worked on with Kyle and we had a full record. It took shape right before my eyes, I didn't really plan any of it, it just happened.

MR: And your end result is Rough & Tumble, a perfect description of the album's approach.

JW: Yeah, it's a tough record. I think it is a committed record. Everything about it seems really hard--I don't mean hard like it rocks so much, but it knows what it's doing. It's got a personality that's pretty bullet proof, it seems to be some sort of creation. There is not a bad track on it--ten of the eleven songs on it sound like singles, and the eleventh track is an acoustic track. It's a very strong record.

MR: I wanted to ask you about the title track "Rough & Tumble." You can tell from what you're saying that despite its aggressive tone, there's a positive attitude in the song as well as a lot of energy on this album.

JW: It's a very committed record, and it's a very certain blues-driven rock record. It's very specific. If you wanna call me out on any lyrics, I can explain them all. I knew what I was doing from the downbeat. I really knew what I was doing even though there was firestorm chaos. We work very quickly.

MR: So, the track "Rough & Tumble" is a #5 record at rock radio. Looks like you have a hit on your hands.

JW: I don't know about that, knock on wood, but it's come out of the box with everybody playing it. We are doing a lot of things like Rockline, and there is a big release party in a couple of days. We are doing really well, I don't know why this time around people are so interested. I think this record has some teeth and I think people were waiting for it. It was #5, #7 last week, and it's gone back up to #5. It's definitely given everyone a run for its money. It's got legs to do it with.

MR: I watched your EPK, and in it, you say, "If you speak from the heart, people will listen from the heart."

JW: And when you hear The Rolling Stones and you're in the car, you're always turning it up.

MR: (laughs) You have another song on the project titled, "If You Ever Get Lonely."

MR: What is the writing process like for you?

JW: It's very spontaneous. I used to carry a notebook with me, but that lasted about a day. I have a house full of notebooks and I don't really seem to use them. A lot of the stuff, I seem to keep subconsciously what I have in my head. When I pick up a guitar, I just start writing songs, the words come out and the melodies come out at the same time. Some writers put the music together then try to put the melody on top, but I tend to get all three at the same time. It comes forward in blasts, and you just seize it while you can, you tweak it and move it around, but it seems to come fully formed. Not complete, but an idea, like the chorus, or the opening to the song, or a catch phrase you hear on radio or TV. You will write it down or you will look at something in the street and you will be lost in thought for a while. I put it in the back of my mind like a collective mind. I look at things or if I read something in a book, I remember it. Even slang and the sound of words...I just like words. I don't know too much on how to write songs, I just write them. I don't really write for the public, I make albums for the public out of the songs I write for myself.

MR: Do you go to your guitar almost as an afterthought, after forming your song?

JW: I bought three new guitars over the last month, three new Telecasters. They are spectacular guitars. The other day, I was looking at one of them, and I was starting to form chords in my head, and yesterday, I picked up another one twice and got an immediate melody and a hook. I've got this new Telecaster that's like an acoustic guitar, I played that, and I got something last night. I don't know, every guitar has a new song in it. The moments making this record and the live record last year, I seemed to have unblocked a part of myself that was very careful about writing and now I'm writing all the time.

MR: What's it like as a co-writer this time out?

JW: With Kyle Cook, it was interesting. I think we're both bright guys and I think we are both clever. If you look at something like a chain of words and you look at the syllables and you understand it immediately...your mind is already moving forward to the rhyming scheme and what you could do to offset the chorus. We were both thinking in the same terms. It's like dancing. You either dance well or you're clumsy. Me and Kyle sort of have that grace. You don't want to make it too polished either. The new record has a rough edge to it all the way through, but if there was any kind of theme on the record it was simplicity.

MR: How did you approach the production for Rough & Tumble?

JW: The stuff in Nashville, with me and Kyle, was done meticulously and though a lot of it was cut live in the studio and then tinkered with, it was meticulous--totally in tune and very thought out. The stuff that I finished the record with, all of the stuff in LA, we cut all of the basic tracks in three days. We didn't stop to think. There was one song that gave me some trouble, I had to come back and cut it again, I cut it three times which was "Further The Sky." I didn't write that song so it was a bit more of a thing to solve, I just got on with it. I like the rawness and imperfection of doing something live, it speaks volumes to me. I think the polished thing can take the soul out of music.

MR: I imagine that in the studio, some of these songs popped out at you like, "Oh my God."

JW: We had a five hour rehearsal in Santa Monica, and I flew the drummer in from Alabama and we all got together. We went in the studio the next day. We had the basic raw tapes of the songs, but we rearranged everything and put new parts in and changed the keys. Me and the guitar player wrote "Rough And Tumble" during that five hour session. So, it was done with extraordinary speed, and I think that maybe that's because I took some time off in the middle. But once I start on something, I don't really let go of it, I know exactly where I'm going and I don't need a particular producer and information. I'm just looking for something that I understand and print to tape.

MR: It's funny that you say print to tape, because at some point today, I'm going to mention to someone without thinking, "Yeah, I taped John Waite."

JW: Yeah, I know--virtual tape because it doesn't exist anymore. The In Real Time album that came out last year was helped a great deal by being done digitally, so we could edit and move and tweak. In the studio, working at that speed, you wonder how you managed to do it all on two inch tape because it's so laborious. It's such a long process, you need a razor blade to cut the tape.

MR: And sadly, nobody is really listening for analog versus digital anymore.

JW: No, they are not. There is a wideness in the analog sound, which is, in some ways, clumsy. Sonics are very subjective anyway, I've heard some brilliant records that have been done digitally and I'm fine with it now.

MR: Considering all the changes that have happened over the last few years including record stores disappearing, do you have any advice for new artists?

JW: Yeah, just make music. Back in the stone age--when it was guys sitting around the campfire at night singing songs about hunting and finding some food--there was no A&R guy sitting there saying it doesn't have a hook. If I was a young kid now, I would just be writing songs. I would be writing from the heart and I would be committing it to virtual tape and making records and putting them out. Basically, that's what I've just done. I made a record away from the record label and then licensed it to them. It's true that all of the shops are closing down. Anybody that wants to find music now can go to iTunes or any of the other sites and get an artist's catalog immediately in very high quality. They still make CDs with audio files, but it's more like something you would listen to through an incredible stereo system. I think it's a level playing field for the artist, there is no such thing as not having a deal. It's about being a troubadour again, it's about making your way through the world through music. If you have to go and ask the A&R guy for $50,000 to make a record, there is something wrong with you. You can make a great record for $5,000, you can. My live album cost $6,000. Who is kidding who, anybody can do this. You don't have to go into somebody's office and ask for the money to do it, you don't have to compromise. Art is back in the driver's seat, and I think that's a wonderful thing.

MR: Absolutely. Now, you recorded a Tina Turner song on Rough And Tumble. Is she one of your influences?

JW: Any African American artist that was making that kind of music, anybody from Sam & Dave to Etta James to Otis Redding, and right up to Tina Turner. They have been the pillars of existence in black music--incredibly powerful, influential music. I like country music too, I liked all the early western songs like Marty Robbins and Frankie Laine--I had a cowboy outfit when I was three years old while I was listening to Frankie Laine. The blues was a big influence on me as a kid, as was Hank Williams, back to country. As was everything. I listen to everything now--The Ink Spots, Ella Fitzgerald, Led Zeppelin--everything. Even the stuff I don't like influences me because it reaffirms what I don't want to do. If you're wide awake, everything will influence you. You can tell in the first four bars, if somebody's got teeth, you just know. I listen to a lot of classic stuff now, I'm not hearing much more that's modern that is original. I have a long life and I'm looking for something that's a hundred percent proof.

MR: You grew up in England and British radio wasn't formatted as much as it was here. What was radio like growing up?

JW: There wasn't that much radio. We had Radio Caroline, which was pirate radio, which just had the movie made about it--a boat stuck out in the Irish Sea somewhere with DJs on it, broadcasting without a license. Everybody in England listened to it. They played The Beatles, they played everything...ridiculous amounts of music. They shut it down in the end because they couldn't control it, the British government was very scared. Before that, we had Radio Luxembourg, which was coming in for, more or less, the service men and American troops abroad. English radio was absolute crap. Capitol radio then fired up, but the BBC was always banishing Beatles records. You couldn't mention anything sexual, you couldn't mention anything with a double entendre, and rock 'n' roll is always about that--it's about sex, fun, living, being wide awake, and chance. The BBC was just awful. Now, it's fragmented, and there is tons of radio in Britain--local, regional, organic stations playing all of these different playlists. Growing up, it was hard to find music. You had to look people up that had those records, you had to go and make friends with them. It was hard to find, and it made rock 'n' roll more romantic. It isn't like you were going to buy a Coca-Cola, you had to go find it.

MR: Europe has a fascinating radio broadcast history.

JW: Europe is a very discerning place. The Parisians are different from the Romans, everybody has their own taste in music, but they are all hardcore fans. They want music, but it's been hard to have that airwave freedom away from the government. There are always people trying to edit and inhibit things that are creative.

MR: I read somewhere that you read Ian Hunter's Diary Of A Rock And Roll Star and that inspired you to come to the States.

JW: It did, I read it, and it was talking about Cleveland and Kid Leo and MMS. The romance of all of the clubs that were having artists come by like Humble Pie and Peter Frampton, all of these great touring bands from that period. I just knew I had to get there. I kind of spent a year and a half in London trying to get a deal in a band, and it all fell through and I came home kind of broke. As soon as I got home to Lancaster, I got a letter wanting me to come to Cleveland. So, it was all of this stuff that was sort of fated. I worked real hard in my life. You can work real hard and go nowhere, but I worked real hard and was given a shot to do things. So, I'm very pleased to have that.

MR: Can you tell us how your group The Babies began?

JW: Well, I got back from America after being in Cleveland, and I got back to London and nothing had happened. A friend of mine invited me along to a meeting with a manager and a guitar player, and I went along to see what would happen. They needed a bass player that could sing and write songs, they didn't have songs. So, I tentatively said I could make myself available for that year. Over that year, we put together a drummer, another guitarist, and a bass player. I played rhythm guitar and after a while went back to bass. After about two years, we got a deal--that was The Babies. That was 1976, so some people reading this wouldn't have been born yet. In London, it was cold, rainy, nowhere to go, and there was no money. You had pictures of Keith Richards taped and you listened to records and stayed in. The girlfriends made sandwiches, and you lived off a pint of beer. It was poverty, in some ways, but highly romantic and full of promise. The promise was America and trying to get out of London and on to the next level. I managed to do that. From that point on, I think, even though some of it was incredibly difficult, it wasn't uphill all the time.

MR: What inspired you to go to solo?

JW: Well, you always want to go solo. The part about The Babies that made it interesting was I was writing all of the melodies, lyrics and chord changes, and they were jumping in and made it a song. It was all in the first person, and that made it sexy. With any band, it's a compromise--you're listening to the drummer, taking in what the guitar player is saying, and you're trying to extract ideas out of them. It's very political. After five years of being in a band with somebody, little things mean a lot. A lot of arguments flair up, you go on the road for three months and you're really bumping heads after a while. When you're young, it's funny, when you get older, it's not so funny. You become more grown up and you're becoming a man, and you don't need somebody's opinion. We all got to that point at the same time. I always toyed with the idea of doing a solo record, but I didn't have any songs lined up to do it. On the way back to England after The Babies broke up, I stayed in New York. I busted my knee up and they put me in a hospital and I spent five or six days staying in an apartment afterward just convalescing. I fell in love completely with New York City, and that was the end of it. I moved to New York City seven or eight months later and went solo.

MR: One of the first hits you had in your solo career was the song "Change" which was endlessly played on MTV.

JW: I knew all of the VJs personally at MTV. It's a small city there, it was still very rock 'n' roll, and it wasn't commercialized. Now, you see a lot of the buildings and you see TGIF and McDonalds, and the record shops have disappeared, the restaurants are being challenged, the bars are disappearing. In the '80s, it was still a great rock 'n' town.

MR: I'm sure it inspired a lot of writing.

JW: The Temple Bar record was written entirely about New York. I was so in love with the city and I still am, I think it's the finest city in the world. I've been here in Santa Monica for eight years, I think I'm making plans to move back to the city, back East.

MR: Can you give us the back story on your hit "Missing You"?

JW: I was finishing the No Brakes album in LA, and I was trying to get home to see my wife--I was married at the time. It was a love song about distance, and it took about ten minutes to write. It was the last song that I wrote for the album, and it just popped out. I knew what I was looking for, but didn't know how to get there. It's persistence, and there it is, #1.

MR: It was a very influential pop song, a lot of bands copped the guitar riff.

JW: It was a great record. It was a very strong record and it was a great single. They were magical times--talk about an album writing itself. That took about a month writing the whole thing.

MR: When you recorded your first solo hit "Change," you were obviously going through changes, right?

JW: I rewrote the verses. A girl called Holly Knight wrote that song, I heard it then wanted to do it. I thought it would be a good single for the New York album Ignition. I rewrote some of the verses, put a spin on it and changed some of the melody and made it my own. At that point, in my head, I was still in The Babies, but in my soul, I was in New York City. I didn't have to put something on that album that was that commercial, but I thought it was a great song that had a great melody.

MR: Later, you ere in the group Bad English. How did that come about?

JW: I made five solo records in a row, then I got real sick of it. I made this record called Rovers Return, and I really said everything I was going to say as a solo. I got a deal with Epic Records, and I remember being in a meeting with an A&R guy, and he was going to find the songs. I said, "Hang on, I just wrote all of these big hits, I can write." He didn't want to know about it, he was going to find the songs and it was going to be difficult. I didn't want to loose the deal, so I tried putting a band together so I wouldn't have to be solo, and it would make it easier to write original material. If it didn't, then I would have to leave. I went to England looking for Johnny Marr. I thought he was a great guitar player, but I couldn't find him. Everywhere I went, I couldn't find him. I kind of gave up, went came back to America, then I somehow wound up with the guys in Bad English. It was like falling downstairs once it started--it wouldn't stop. It wasn't the original idea, but all of those things that go awry usually turn out to be great. We had two and a half years together, toured the world, and had a great run.

MR: And big hits. Epic seemed really behind you, they wanted to break their new act.

JW: Epic was fantastic...Polly Anthony there, she was the Queen of Promotion. She put us on all of the great radio shows, and the record broke immediately because of Polly. You couldn't have been with better people to work with. It was the best. I think the problem was that they wanted a second album really quickly, and we went on the road for a year, and we weren't really writing on the road. By the time we got back, we were exhausted. They wanted a second record and we said, "Oh, we will try." I think we should have just taken six months off, I think it would have really helped.

MR: Then there wouldn't have been such a Backlash, so to speak...

JW: (laughs) Very clever. I think that was expected, I knew if we were to make a second record, we were going to get destroyed. It had a great cover. It was a good record, but we just couldn't deal with each other anymore. We had been with each other for two years without any time off from each other. That thing I said before, when you're a kid, being in a band is great, but when you get older you've got wives, kids, families, divorced wives. You have responsibilities, you can't just be in a band all the time. You have to live a life.

MR: What is the song you identify with the most on Round & Tumble?

JW: It would probably be "Further The Sky." There are two cover songs on the album. One is Tina Turner's "Sweet Rhode Island Red," and the other one is writer Gabe Dixon's "Further The Sky." I asked Alison (Krauss) what she would suggest because I was going to make an album of acoustic songs. I thought she could suggest some very dark, moody, guilt ridden kind of songs I could sing. I was really interested in doing that, but then I thought, "No, I can't do that. It wouldn't hang with the Kyle tunes that we wrote." She suggested "Further The Sky." Me and Allison go back a long way, and I thought she was sending me a message, and when I sang it, I thought I was sending her a message. It was kind of a beautiful thing. It's really a beautiful song and it's entirely live. I just took a run at it and sang it. That's probably my favorite thing.

MR: What's the label experience like these days?

JW: Frontiers is the record label in Europe. They are the biggest company in Europe, and the head of the label is a great guy. He has put me in all of the magazines, and there is a huge amount of press. We are going over to tour again in April. We are probably going to break Europe this year. Over in America, it comes out on the 22nd of February, and it's on Model Records which is distributed by Universal, so that is also a big deal and they have done a fantastic job as well. We are getting all sorts of airplay, and like I said, the single was #5. Everybody digs the record. I'm really happy, the band would love to work. We just played on Saturday night in New Orleans, and Kyle Cook is now our guitar player. He is going to be our guitar player for the next six weeks while we try and find a permanent guy. Kyle stepped in, and it was our first gig together on Saturday and it was fantastic. We are all looking forward to Europe we are doing a string of dates in America before we go, but God bless it. If the thing sells a hundred thousand copies, everybody is screaming and laughing. If it sells five thousand, everybody will be doing the same thing. Everybody is just so behind the record. I'm just grateful to be in the situation and I'm really proud of the record. It's going to be a good time.

MR: It's good to know that everybody is screaming and laughing, congratulations. One last thing, how have you grown over the years?

JW: I would like to say I was the same person, I think my heart's the same. I've just seen a lot of the world, and I know how much has changed. I've seen such a great deal. I spent eighteen years there and that was such a great time of my life. I've seen such a lot, and I've worked with such great people and I've seen so many miles...it still means a lot to me to climb up on stage and sing these songs. On Saturday night in New Orleans, the curtains opened, it was a sold out show, and it still means as much to me as it did when I was a kid. I hope I'm doing this in five years time. All I know is that I've learned to love what I do.

Tracks:

1. Rough & Tumble

2. Evil

3. If You Ever Get Lonely

4. Skyward

5. Sweet Rhode Island Red

6. Mr. Wonderful

7. Further The Sky

8. Love's Goin' Out of Style

9. Better Off Gone

10. Peace of Mind

11. Hanging Tree